A Future to Her Taste

The Gender Politics of Diet in Late Nineteenth-Century Speculative Fiction

By Lucy Coleman

Abstract

In this dissertation, I argue that the speculative fiction of the 1880s encodes cultural anxieties about the shifting status of women through representations of diet. Drawing on Carol J. Adams’ The Sexual Politics of Meat (1990), I examine how vegetarianism is linked to feminine passivity in early feminist utopias such as Mary Lane’s Mizora (1889) and Elizabeth Corbett’s New Amazonia (1889), where meatless diets support peaceful yet emotionally restrained societies. These texts present carnivorism as a masculine practice, reaffirming a historical myth which also influences the dystopian responses to women’s rights literature. The anxieties expressed in these dystopias are grounded in the ideals articulated by early feminists like Lane and Corbett. In William Butler’s Pantaletta (1882), the success of the suffrage movement leads women to adopt masculine appetites, revealing Butler’s fear that female empowerment would emasculate men. In Anna Dodd’s The Republic of the Future (1887) and William Henry Hudson’s A Crystal Age (1887) the pursuit of gender equality coincides with the purification of diet and the erosion of sexual desire. Despite the absence of material suffering, the male protagonists in both texts ultimately reject these futures due to a perceived loss of passion and erotic polarity. Across the texts, hierarchies of race, gender, and species frequently reinforce one another, with eugenic logic underscoring many utopian ideals. Configurations of appetite – both culinary and carnal – serve as key indicators of late nineteenth-century attitudes towards female empowerment, revealing a persistent fear that desire would disappear alongside patriarchy.

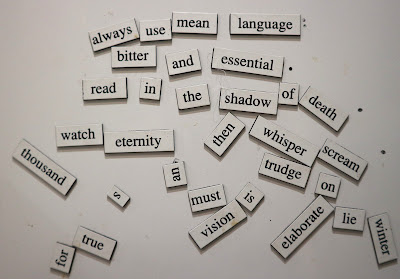

Edward Burne-Jones, ‘Freize of Eight Women Gathering Apples’ (1876)

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor Andrew Bennett for his insight and encouragement, without which I would never have found my focus. I would also like to offer my sincerest apologies to all the animals I ate while writing this dissertation.

Introduction

The 1880s marked an explosion in speculative fiction, shaped by the growing tides of social activism in Britain and America. As campaigns for women’s rights, animal welfare, and domestic reform gained momentum, literary minds turned to the morally transformed future. A striking pattern emerges in the diet of these imagined futures: where nineteenth-century gender roles are reconfigured, meat is often taken off the table. This recurring connection between vegetarianism and female liberation reflects a broader network of cultural anxieties, illuminated by comparison to Carol J. Adams’ The Sexual Politics of Meat (1990). Adams argues that meat-eating symbolically affirms masculinity while contributing to the objectification of both women and animals, sustained by the enduring myth that men have a greater biological need for meat than women.[1] Though most modern consumers are now detached from the physical processes of farming and hunting, the archetypes of man as ‘hunter’ and woman as ‘gatherer’ persist in the cultural framing of vegetarianism as a feminine diet.[2] These associations are reflected in the dietary surveys of the mid-nineteenth century: as Edward Smith observed, women, despite cooking the food, were ‘the worst-fed of the household.’ They would ‘eat the potatoes and look at the meat.’[3]

By the 1880s, technological advancements in the home had allowed many middle-class women the freedom to engage in social activism, fuelling campaigns for both women’s suffrage and animal rights.[4] For example, the cooking of vegetarian food in the home and the proliferation of female-authored cookbooks led the first British Vegetarian Society to quadruple its membership across the latter half of the century.[5] As Jean Pfaelzer argues, women were considered the ‘moral wardens of the new culture,’ becoming figureheads for both the animal rights and women’s rights movements.[6] These causes, aligned in what Edward Bellamy called the ‘great wave of humane feeling,’ became entwined in the public conception of progress.[7] This likely contributed to the joint representation of vegetarianism and female liberation in the literature of the decade. The crest of this moral wave proved fertile ground for the utopian imagination, spawning works like Mary Lane’s Mizora (1889) and Elizabeth Corbett’s New Amazonia (1889). These envisioned futures of moral refinement and female authority, framing vegetarianism as a natural byproduct of women’s liberation. In response, conservative writers William Butler, Anna Dodd and William Henry Hudson projected dystopias in which the absence of meat signals not moral progress, but the erosion of masculine identity and romantic agency.

Adams’ framework reveals an internalised language of subjugation in the utopian texts, whilst also indicating anxieties around emasculation in the diets of the dystopian works. Vegetarian food, in both cases, is associated with passivity and stagnation, while meat is upheld as a symbol of societal and sexual passion – associations which are embedded in language itself: to ‘vegetate’ is to ‘lead a dull, monotonous life,’ while the ‘meat’ of the matter is a subject ‘of importance or substance’ (OED). Even as Lane and Corbett attempt to sever women from the ‘corrupting’ vices of men – meat-eating, drinking and smoking – their peaceful yet dispassionate societies reinscribe Victorian ideals of female purity, passivity and whiteness. This speaks to a broader fallacy within utopian writing, which often ‘reflects real conditions at the same time as it opposes them.’[8] As such, the authors restate the racist ideology of the decade through the eugenic logic of their futures. In all the works I consider, hierarchies of race, gender and species inform and enforce one another.

If, as Adams states, ‘one’s maleness is reassured by the food one eats,’ then the dystopian responses to women’s rights literature reveal more than dietary preference.[9] These authors upend the utopian vision of purity, imagining futures stripped not only of meat, but of passion and romance. They project their anxiety that with women’s liberation would come the collapse of masculine desire, suggesting that in ‘feeding’ women, men would go hungry. This fear of emotional and sexual starvation is encapsulated in William Butler’s epigram, taken from Tennyson:

For woman is not undeveloped man,

But diverse: could we make her as the man

Sweet love were slain.[10]

In this dissertation I explore how appetite – both culinary and carnal – functions as a symbolic framework through which late nineteenth-century writers articulate their anxieties about gender, desire and social change. By examining the speculative fiction of this pivotal decade, I argue that fears of social reform are negotiated not only in the bedroom or the ballot box, but at the dinner table.

What Feeds the Female Future?

Between 1880 and 1881, readers of the Cincinnati Commercial were introduced to ‘The Narrative of Vera Zarovitch’, which detailed the discovery of a world ruled by blonde, vegetarian women beneath the Arctic ice. This serial garnered more attention than other articles in the regional newspaper, and by the end of the decade it had been compiled into a novel renamed Mizora: A Prophecy.[11] At nearly the same time, across the Atlantic, Elizabeth Corbett published New Amazonia: A Foretaste of the Future, a utopian vision also dominated by blonde vegetarian women. Each work’s subtitle reveals its author’s intention to describe a potential future, though only Corbett’s work contains actual time travel. Whilst there is no evidence that the authors knew of each other’s work, the similarities between their envisioned societies are extensive. Both are underpinned by the assumption that to imagine a truly liberated future, one must change what is on the plate as well as who is at the head of the table. In this chapter, I use Adams’ framework to examine vegetarianism in both works as an expression of idealised femininity, suggesting purity, temperance, and moral superiority. In attempting to extricate womanhood from the ‘corrupting’ appetites of the masculine world, these authors offer visions of female empowerment that paradoxically reaffirm Victorian ideals of restraint and passivity. The utopia, here, is not a feast, but a fast.

Mary Lane’s Mizora: A Prophecy (1889)

Lane’s novel follows Vera Zarovitch, a wealthy Russian radical, who is exiled to Siberia and shipwrecked in the Arctic. As an imperialist adventure romance, Mizora adheres to the genre’s hollow earth trope, identified by Heidi Hansson, as Zarovitch is swept through a whirlpool at the North Pole into a lush subterranean paradise named Mizora.[12] The overworld’s carnivorism (particularly Zarovitch’s disgust at eating ‘raw flesh and fat’ with the Inuit population) contrasts sharply with Mizora’s exuberant horticulture (p.11). Zarovitch is ‘refreshed’ by vegetation, recording ‘the fragrance of tempting fruit’ and ‘numerous orchards’ in her first impressions of the land (pp.11-14). She discovers this world to be populated exclusively by identical muscular women whose moral purity causes them to eat ‘chemically prepared meat,’ restating the Victorian connection between femininity and superior morality (p.18). The Mizorans have eliminated men and those with ‘dark complexions,’ suggesting a troubling endorsement of eugenics which, as Katherine Broad argues, problematises the novel’s feminist message (p.92). [13] The drawbacks to Lane’s feminism are worthy of examination, however, as despite expressing discomfort with Mizora’s racial exclusions and shunning of individuality, Zarovitch ultimately chooses to uphold its ideals, returning to the overworld to promote universal education and female suffrage (p.92). Lane thus enacts what Pfaelzer identifies as the utopian paradox: she restates the eugenic logic of her time, just as she ‘reproduces patterns of belief about femininity, in the society [which] seeks to transcend them.’[14] Mizoran womanhood, in its pursuit of universal beauty, ‘embodies stasis as a female value,’ having abandoned ‘the energising forces of personality.’[15] Lane’s feminism, then, is qualified by the passive, racialised ideal of Victorian womanhood.

Whilst Pfaelzer names Mizora a ‘proto-lesbian vision of the future,’ I do not believe that Lane’s elimination of men necessitates lesbianism so much as it neutralises sexuality entirely.[16] Mizoran society has discarded not only the vices which it associates with men such as meat-eating, alcohol and tobacco consumption, but also sexual desire itself. Reproduction occurs parthenogenically, allowing Lane to sidestep the Victorian dichotomy between the celebration of motherhood and the vilification of sexuality. Principal Grey proudly explains, ‘we have got rid of the offspring of Lust’ (p.130). Broad argues that maternal affection here replaces carnal desire, forming a sanitised ‘replacement for sexuality that alters but does not eliminate feelings of intense desire.’[17] Vegetarianism, in this sense, becomes a natural extension of Mizora’s repression of ‘impure’ appetites, aligning its diet with other palatable expressions of femininity. Vegetarianism is also indicative of idealised femininity because it suggests a harmony with nature. As Sherry Ortner observes, literary culture has long described women as more closely a ‘part of nature’ than men.[18] Lane’s descriptions of Mizora’s ‘voluptuous beauty’ and ‘delicate green’ embody this connection, imbuing nature with femininity (pp.11-15). The Mizorans, being ‘part of nature,’ navigate their environment with ease, unlike Zarovitch’s male crew, who are shipwrecked in the Arctic (p.10). They are first observed on a boat ‘shaped like a fish, mov[ing] gracefully and noiselessly through the water (p.15). In refusing to kill animals or dominate their environment, the Mizoran women affirm their idealistic alignment with nature.

The novel’s central novum – the scientific innovation which drives the plot – further deepens Lane’s connection between nature and femininity. Mizoran women reproduce using ‘the germ of all Life, the MOTHER,’ a female cell which allows parthenogenic reproduction. This female origin means that ‘even in [Mizora’s] lowest organisms, no other sex is apparent (p.103). Lane’s imagined biology reinforces the idea that femininity is both the origin and essence of nature, becoming more conceivable half a century later with the scientific discovery that all embryos develop phenotypically female before differentiation.[19] Her fusion of animal, woman and environment is reflected in her descriptions of the Mizorans having ‘animal spirits,’ and voices like ‘the love notes of a bird to its mate’ (pp.13, 16). Lane feminises both the flora and fauna, likening one piece of fruit ‘whose beauty no art could represent,’ to the ‘tempting lips’ of the woman who eats it, connecting the beauty of the Mizoran food to its consumers (p.18). The Mizorans’ clear relation to the organic life of their societies resonates with Adams’ critique of the literary tendency to ‘animalise women and feminise animals.’[20] Zarovitch’s guide, the Preceptress, reaffirms this dynamic in recalling that ‘woman was a beast of burden’ to man (p.95). Yet Lane subverts this historical oppression when the Preceptress declares that women resolved to ‘gather the reins of government in their own hands’ (p.100). In Mizora, the hierarchies of man over woman and human over nature are dismantled in tandem. Though Victorian ideals of feminity are preserved in the utopians’ sexual purity, passivity and beauty, Lane subverts the language which degrades women by likening them to animals. She affirms female authority in the vegetarianism of her society, suggesting that women’s power is rooted in their ability to harmonise with nature.

Elizabeth Corbett’s New Amazonia: A Foretaste of the Future (1889)

Elizabeth Corbett’s vegetarian utopia, like Lane’s, uses diet to construct a feminised moral order which is exclusionary and repressive in its restatement of Victorian ideals. She differs, however, in her inclusion of male characters, allowing the connection between vegetarianism and femininity to be bolstered by the inverse relationship between men and meat-eating. New Amazonia opens with Corbett’s unnamed female narrator attacking the biblical notion that because ‘woman was but made from the rib of man’ she could ‘never be his equal.’[21] Having fallen asleep at her desk, she awakes to find herself in a paradisical garden, alone with a solitary man – Augustus Fitz-Musicus, an antifeminist aristocrat, who had awoken in New Amazonia after smoking cannabis in a gentlemen’s club (p.9). This subtle reconfiguration of Eden reimagines Christian doctrine, suggesting that women were made in the image of a female god, making men the secondary sex (p.75). As in Mizora, the landscape of female-dominated New Amazonia is first described with ‘trees laden with luscious fruits,’ reaffirming the association between a futuristic female society and abundant natural food (p.9). The seven-foot, blonde population includes a small number of men for reproductive purposes, but these are content with exclusion from governance (p.45). Yet, like Mizora, this utopia is underpinned by eugenic thinking: those with ‘the slightest trace of disease of malformation,’ or who fail to adhere to the ideals of beauty or whiteness are ousted (pp.40, 11). While Corbett’s narrator embraces her freedom, Augustus resents his marginalisation and is eventually threatened with execution by the New Amazonian authorities. Both characters return to the nineteenth century by consuming the same cannabis that first caused Augustus to time travel.

The inhabitants of New Amazonia eat ‘much fruit, all of which was marvellously sweet and luscious,’ with ‘no dishes prepared from animal food’ (p.16). Carnivorism, they believe, is ‘a habit which induces coarseness of mind and body, and robs both of the true beauty, and vigour furnished by a vegetable diet’ (p.52). Like Lane, Corbett links meat-eating with impurity, rejecting both alcohol and flesh as masculine indulgences. Principal Grey explains, ‘an intoxicant cannot be procured in the island’ (p.52). The first women of New Amazonia abandoned meat not for political reasons, but for their moral and physical ‘inability to kill animals’ (p.52). As Theophilus Savvas notes, Corbett thus connects ‘slaughter and flesh-consumption with male power and control,’ reinforcing Adams’ view of vegetarianism as historically feminised.[22] The New Amazonians’ aversion to violence contributes to their idealised femininity: as Pfaelzer notes, the perfect Victorian woman was ‘seen as instinctively peaceful and pure.’[23] Vegetarianism is the natural extension of this ideal. Corbett’s levelling of the human-animal hierarchy is, like Lane’s, reinforced through moments of blurred species distinction. Her population inoculate themselves with ‘the nerves of young and vigorous animals’ to preserve their health, whilst ensuring that these creatures ‘do not suffer one little bit’ (pp.78, 83). Species blur together in New Amazonian art, where ‘neither walking biped, running quadruped, nor flying bird [is] painted aright’ (p.116). Principal Grey explicitly invokes the animalised rhetoric of subjugation, recalling that woman was once ‘something better than [a man’s] dog, and something dearer than his horse’ (p.36). As in Mizora, New Amazonia’s vegetarianism creates an idealistic affinity between women and animals, suggesting that female governance would minimise suffering across species.

Corbett’s inclusion of male characters further clarifies the gendered politics of diet. Though the New Amazonian food ‘supplied all the wants of the body,’ Augustus remains unsatisfied, lamenting, ‘it’s a confounded nuisance not to be able to get hold of a bit of butcher’s meat’ (pp.59, 103). In contrast, the narrator finds her meals ‘very appetising’ (p.117). Augustus’ complaint aligns with Adams’ claim that meat-eating is culturally coded as a crucial aspect of masculinity.[24] His frustration grows after he fails to attract the New Amazonian women, reinforcing Adams’ argument that ‘where there is (anxious) virility, one will find meat-eating’ (p. 67). His desire for meat emerges alongside his emasculation: he is first ridiculed for identifying as a man (‘A man! Never!’), then clothed in the national costume, which is implied to be a dress, and finally sentenced to death for refusing to wear it (pp.13, 65, 142).[25] Augustus’ character allows Corbett to dramatise a loss of masculine agency in response to female control, linking her abandonment of meat-eating with the erosion of masculinity. Augustus’ ‘anxious virility’ is induced not only by the vegetarianism of New Amazonia, but its wider suppression of sexuality. As in Mizora, New Amazonia disparages carnal desire. ‘All our most intellectual compatriots, especially the women,’ says Principal Grey, ‘prefer honour and advancement to the more animal pleasures of marriage and re-production of species.’ (p.81). Though marriage still exists, it is viewed as a distraction from intellect, with ‘perfect clearness of brain’ requiring ‘the celibate state’ (p. 82). Though Corbett, like Lane, reaffirms restrictive gender roles in her work, Augustus’ repeated exclusion – from romantic, political, and culinary spheres – exemplifies the radical extent to which women’s rights literature was able to attack traditionally masculine desires and roles. Both authors suggest that female power is secured only through the erasure of masculinity, necessitating a meatless diet. While to Lane and Corbett, vegetarianism symbolises moral progress and feminine refinement, their conservative contemporaries reframe the same dietary shifts as dystopian threats. The following chapter examines these antifeminist responses, where the absence of meat reflects a perceived loss of male agency and sexual potency.

‘Timorous and Jealous Male Bipeds’: The Diet of the Antifeminist Dystopia

Examining aversion to vegetarianism in male-authored Victorian fiction, Savvas briefly notes the concern that ‘vegetarianism was a ‘first step’ in the rejection of carnality.’[26] Expanding on this, I consider three lesser-known works of gender-based dystopia from the 1880s, reading diet as a gauge of attitudes towards sexuality and social reform. As Pfaelzer notes, the dystopian genre peaked in popularity at the end of the 1880s, directly corresponding with heightened activity in the female suffrage campaign.[27] As such, Pantaletta (1882) and The Republic of the Future (1887) adopt speculative settings to deliver explicit messages against women’s suffrage and animal welfare, using reductio ad absurdum caricatures to discredit the movements. In contrast, William Henry Hudson’s A Crystal Age (1887) complicates the dystopian frame. Hudson’s speculative world does not neatly align with Eric Rabkin’s categorisation of utopia versus dystopia which depends on authorial endorsement, so it is more accurately described as simply speculative.[28] In each case, the future of female empowerment entwines dietary change with a loss of male agency, though Hudson’s view provides the most nuance. He offers a vision of social equality sustained by vegetarianism, at the sole cost of romantic and sexual passion. His conclusion suggests that this sexuality, even in its destructiveness, may be worth preserving above all else.

William Butler’s Pantaletta: A Romance of Sheheland (1882)

In her introduction to New Amazonia, Corbett laments the rise of female-authored anti-suffrage articles as ‘treachery perpetrated towards women by women,’ dismissing them as ‘hoaxes got up by timorous and jealous male bipeds’ (p.1). Her description aptly fits Pantaletta, initially published under the name Mrs J. Wood. Described by Peter Sinnema as a parody of Mizora, Pantaletta follows General Gullible, a conservative American, who flies through a hole in the North Pole and lands in Petticoatia – a society ruled by masculine women called ‘shehes,’ who feminise and subjugate the male ‘heshes.’[29] Despite the unsubtle naming of Pantaletta’s protagonist, Gullible, Mrs J. Wood’s true identity would not be revealed until 2011, when Mary Ockerbloom attributed the work to newspaper editor William Butler.[30] Gullible is forcibly feminised and seduced by Petticoatia’s president before joining an anti-shehe resistance led by Razmora, Butler’s answer to Lane’s Preceptress. Razmora laments that ‘the females […] have inherited with the pantaloons all the vices and wickedness of men,’ including ‘chewing fatty substances’ and snuff, while ‘man has become the sex from which stainless purity is required’ (ch.14). While the shehes eat meat, Gullible is served mostly ‘luscious fruits’ (ch.9). Therefore, though this society is not vegetarian, Butler calcifies meat-eating as a masculine act usurped by women. Like Lane and Corbett, Butler connects femininity with nature, but for satirical ends. His shehes bear hyper-feminine, floral names like ‘Lilibell’ and ‘Pansy,’ contrasting with their violent, ‘unfeminine’ behaviour. The scorned captain, Pantaletta, for example, attempts to murder Gullible for his refusal to shave his moustache. Ultimately, he escapes, swapping identities with another American, who marries the president while he returns to the overworld to prepare an invasion.

Butler’s dystopia directly attacks the suffrage movement, utilising the gendered dynamics of diet to undermine the cause. Here, the ‘worship of progress’ in the late nineteenth-century is transformed to an ‘unholy spell of madness,’ spawning demonic suffragettes like Pantaletta (ch.12). She ‘deifies’ the ballot, screaming ‘give us the ballot – the ballot!’ amidst other ‘incoherent ravings’ (ch.12, 17). Petticoatia’s environment, though Edenic, ‘rivalling the garden of our first parents in beauty,’ becomes a satirical scene of original sin, as Butler describes the ballot as the ‘forbidden fruit’ which led women to reject ‘the Bible – the family – society’ (ch.4, 12). The result is a binary inversion of gender roles, supporting Justin Prystash’s claim that sex-focused speculative fiction often ‘calcifies the Victorian gender binary,’ simply ‘putting a beard on the Queen of Hearts.’[31] Butler’s central fear is that women’s empowerment will emasculate men – a dynamic endorsed in works like New Amazonia. Like Augustus, Gullible’s gender is contested upon arrival: ‘her mind is diseased. Take her away and guard her’ Pantaletta says (ch.4). He is dehumanised for his nonconformity in Petticoatian newspapers, becoming ‘the Thing,’ a ‘snorting mountain of flesh,’ and being sentenced to ‘indignities’ like beard-shaving and wearing rubber breasts to avoid execution (ch.6, 8). This extends Augustus’ comic emasculation into horror, exposing the deeper anxiety beneath such tropes. Yet even as Butler critiques Petticoatia’s dehumanisation of those who do not conform, he restates his superiority over women by animalising them. His female characters ‘crow like hens’ and ‘low like kine,’ and when Pantaletta lashes out he calls her an ‘infuriated beast’ (ch.14).

Butler is also concerned with the future of sexuality, believing that ‘like the positive and negative qualities of the magnet’ the loss of gender distinctions ‘would render man and woman mutually unattractive’ (ch.12). Butler’s population are ‘angular,’ ‘ugly-faced,’ and ‘sadly deficient in looks’ (ch.5, 6). He suggests that the suffrage movement will reduce male sexual agency, as not only do his women ‘chew fat’ but they also objectify men as ‘meat’ through Adams’ framework. His shehes ‘frequent dens of infamy,’ implying a culture of male prostitution (ch.14). As Sinnema argues, Butler’s vilification of the shehes is rooted in their ‘uncontained sexual appetites.’[32] Pantaletta poses a sexual threat, describing Gullible as ‘cold meat,’ and calling on her ‘butchers’ to ‘strip’ and ‘smother’ him, ensuring ‘the skin will not be disfigured’ (ch.17). This pseudo-necrophilic and cannibalistic passage invokes Adams’ description of butchery, which ‘proclaims our intellectual and emotional separation from’ the object’s rights to existence.[33] Here, the suffragette becomes literalised as a female butcher, objectifying and consuming the male body. Butler’s horror at reversed power dynamics aligns Pantaletta with the racialised cannibals he later introduces: the ‘dark-skinned, naked’ tribe who prepare a white man for dinner, similarly insisting that ‘no disfigurement’ occur (ch.20). Racist stereotypes thus bolster Butler’s antifeminist stance, shown elsewhere in his philosophy that ‘suffrage is not a natural right, since aliens who pay taxes may not vote. […] It is between the sexes as between the races, the strongest rules’ (ch.12). Butler therefore interconnects racial, animal and gendered hierarchies to articulate and enforce his position. His narrative feeds on male anxieties, suggesting that in empowering women, society would shift the exploitative dynamics of meat-eating onto men, leading to their objectification and emasculation.

Anna Dodd’s The Republic of the Future; or, Socialism a Reality (1887)

Had the Illustrated American not published a biography of Anna Dodd in 1891, she might easily have been mistaken for one of Corbett’s ‘hoaxes.’[34] Adopting a more restrained approach than Butler, Dodd’s epistolary satire critiques the ‘wave of humane feeling’ which encompassed animal rights, women’s suffrage and socialism, through the dystopian vision of a hyper-rationalised metropolis. She adheres to the trope identified by E.M. Cioran as ‘the nightmare of the perfect city,’ where ‘all conflict would cease; human wills would be throttled or mollified, and there would reign only unity.’[35] Her narrator, Wolfgang, a Swedish tourist in the year 2050, recounts his experience in ‘the Socialistic City of New York,’ where technological advancement has eliminated the need for labour, creating a ‘land of dead of dead equality.’[36] Dodd dates this decline into apathy to the year 1900, firmly linking it to the social movements of her time (p.37). As in Pantaletta, Dodd predicts that women’s suffrage would result in dominance over men, with women’s votes being ‘polled ten to one over’ theirs (p.38). Pfaelzer describes this as Dodd’s attempt to ‘mock the conjunction of socialism [and] feminism’ in utopian writing. [37] Dietary reform can be added to this joint attack, as Dodd’s New Yorkers are sustained by bland, governmentally prescribed nutrition ‘pellets,’ negating the need for kitchens, dinners, and with them, the domestic sphere (p.28). She roots this dulling of diet in calls for female emancipation, as the population believe that ‘when the last pie was made into the first pellet, woman’s true freedom began’ (p.31). Despite claiming that their ‘greatest desires’ are fulfilled, the citizens live in subdued dissatisfaction, and Wolfgang readily returns to his ‘barbaric Sweden,’ where society is ‘chaotic and unformed,’ but still ‘tremendously alive’ (p.85).

Like Butler, Dodd constructs reductio ad absurdum caricatures of social activists, directly attacking the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals which had been founded in New York two decades earlier.[38] She invents the ‘Society for the Prevention of Cruelty among Cetacea and Crustacea,’ who deploy ‘sub-marine missionaries,’ to ‘punish’ fish for eating other fish, and provide ‘proper Christian food’ as an alternative (pp.11-12). Her absurd presentation of animal rights activism dismisses the movement as misguided and needless sentimentality, which would lead to a condemnation of meat-eating in the animal kingdom as well as in the human population. One such activist laments that the fish ‘appear to have been born […] without the most rudimentary form of the moral instinct,’ suggesting that the morality argument behind vegetarianism goes against our animal nature (p.12). Dodd dismisses women’s rights activism with similarly absurd caricatures. For example, her women are ‘not to be degraded’ by manual labour, leading to the prohibition of ornate picture frames as they are too difficult to dust (p.33).

Echoing Butler’s thinking, Dodd suggests that gender equality would curb attraction between men and women, describing a ‘gradual decay of the erotic sentiment, […] due to the peculiar relations brought about by the emancipation of woman’ (p.37). ‘They used to flirt – wasn’t that the old word?’ one inhabitant remarks (p.30). Dodd partially blames the androgyny of the population, as the women ‘dress so exactly like the men that it is somewhat difficult to tell the sexes apart,’ and beauty is discouraged, having once ‘enslaved’ women (pp.26, 36). Marriages remain, but they are ‘more nominal than real,’ and lack passion as ‘husband and wife are in reality two men, having equal rights’ (p.40). Technological advances in cooking have aided this dissolution of intimacy, as food can be eaten anywhere, meaning there is ‘no common board’ (p.40). This has helped erase the word ‘home’ from the population’s vocabulary (p.40). If, as Maurice Minton claimed in 1891, ‘Edward Bellamy drew much of his inspiration’ from Dodd, then this element of her dystopia may have indirectly shaped his view in Equality that vegetarianism and women’s liberation would rise together.[39] Bellamy wrote that ‘the revolt against animal food coincided with the complete breakdown of domestic service and the demand of women for a wider life,’ linking women’s freedom from domesticity to a simplification of diet.[40] In Dodd’s view, suffragettes seek to dismantle the kitchen, in turn eroding the foundations of the wider marital and domestic spheres.

William Henry Hudson’s A Crystal Age (1887)

Unlike Butler and Dodd, whose dystopias mock feminism by exaggerating its outcomes, Hudson offers a sincere but unsettling alternative: a peaceful, egalitarian world where the cost of harmony is desire itself. Writing in the same year as Dodd, Anglo-Argentine naturalist William Henry Hudson critiques utopian passion – specifically, its absence – from a nuanced perspective. Though Clifford Smith’s foreword describes A Crystal Age as ‘joyously free from satirical purposes,’ a ‘poet-naturalist’s view of things as they should be,’ I believe that Hudson’s speculative world cannot be considered a utopia.[41] The novel opens with Smith, a naturalist like Hudson, falling from a cliff while cataloguing local fauna (p.1). He emerges from the earth ‘like a mole,’ ‘oddly enough, on all fours,’ in a ‘pretty, primitive wilderness,’ several centuries later (p.2). Like Pantaletta’s Gullible, Smith is immediately dehumanised upon arrival, described as ‘some strange, semi-human creature’ by the land’s androgynous inhabitants, ‘the Family’ (pp.6, 177). Their unisex clothes are styled like ‘the skins of pythons,’ suggesting a utopian harmony with the natural world (pp.14-5). Their respect for nature necessitates vegetarianism, leading to increased lifespans. Elana Gomel describes them as identical ‘as if they had all emerged from a Burne-Jones painting,’ with a universal beauty like that of the New Amazonians.[42] She notes that ‘the absence of gender is closely connected with the elimination of desire’ in the novel, a theme repeated across all three dystopias.[43] They have abandoned meat-eating, money, cities, and crucially, sexual appetite. Darko Suvin describes the Family as a ‘beehive-type matriarchy,’ presided over by Chastel, who alone bears children, residing in the ‘Mother’s Room.’[44] This allows equality between her sons and daughters, as marriage and sexuality do not affect their lives. Smith falls in love with Chastel’s daughter Yoletta, only to discover she is incapable of sexual feeling. Despairing, he drinks poison, declaring that ‘this colourless existence without love’ is worse than madness (p.305). The conclusion reflects Hudson’s belief that there could be ‘no perpetual peace till fury’ and passion ‘had burnt itself out.’[45] This is no pastoral ideal: as Suvin writes, for Smith ‘the only solution is death.’[46]

Hudson’s reverence for nature, drawn from his years as an ornithologist on the Argentine Pampas, ‘virtually fused’ to his horse, is embedded in his vision of human-animal coexistence.[47] Prystash situates Hudson’s pastoral vision within a broader naturalist longing for ‘transcendent stasis’ against the ‘ceaseless change’ of civilisation, though for Hudson this stasis comes at the cost of passion.[48] In his society, animals live without fear. Smith’s horses ‘walk to the plow’ and place themselves before it, and birds perch fearlessly on people’s shoulders (pp.113, 54). This leads to beneficial evolution across species: dogs become more intelligent and humans gain ‘owlish vision’ (pp.74, 293). As in other works, racial stereotypes frame meat-eating as barbaric to emphasise support for vegetarianism. Smith attributes the birds’ fearlessness to ‘the fact that there were no longer any savages on earth’ to eat them (p.289). Hudson’s naturalist ideal is therefore that animals and humans, in establishing respect for one another, would advance together in peace.

It is an ideal, however, which Hudson suggests is incompatible with Victorian masculinity. Smith is ‘annoyed’ by the abundance of animals, missing ‘the streaky rasher from the dear familiar pig,’ alongside coffee, tobacco and alcohol – all masculine vices in Adams’ framework (pp.10, 111).[49] His views on gender reinforce this masculinity, believing that women’s ‘brains are smaller,’ and that ‘some people hold that women ought not to have the franchise, or suffrage […] I hope they’ll never get it’ (pp.98-9). Smith’s matrimonial advances on Yoletta are similarly conservative, likening her to purchasable cattle: he wonders ‘how many years of toil would be required to win Yoletta’s hand,’ and jokes about putting ‘a rope around [her] waist’ (p.107). Smith’s romantic frustrations mirror his feelings towards their vegetarian diet, as both leave him unsatisfied. The walnuts ‘had a curious effect on me, for, whereas before eating I had not felt hungry, I now seemed to be famishing’ (p.9). He is ‘disappointed’ with the insubstantial ‘whitey-green crisp stuff’ he is served at dinner (pp.9, 53). Like the walnuts, every taste of Yoletta’s love increases Smith’s hunger for her – ‘her delicious words maddened me!’ he exclaims (p.227). He watches her with a ‘hungry look,’ and is described as a ‘hungry animal that wanted to devour [her]’ when they kiss (pp.145, 155). Like Dodd and Butler, Hudson envisions a future starved of sexual and emotional fulfilment in its equality. Chastel is horrified by Smith’s description of marriage, calling it a ‘repulsive idea’ which would fill the earth with ‘degenerate beings, starved in body and mind’ (p.196). As a sex-averse matriarch, she is an emblem of the dystopian fear that social equality would relegate passion to history. For Hudson, Dodd and Butler, it is not the present but the ‘liberated’ future which leaves humanity ‘starved in body and mind.’

Conclusion: Forbidden Fruit

At a surface level, the prevalence of vegetarianism in late nineteenth-century speculative fiction reflects the perceived interconnectedness of contemporary social reform movements. The greater freedom allowed by domestic technology led women to front campaigns both for gender equality and animal rights, entwining the two in visions of a ‘liberated’ future. In utopian and dystopian projections, women’s demand for a change in domestic duties prompts a reconfiguration of cooking practises, and consequently, of diet.

Beneath this surface, however, lies a subterranean world of symbolic associations, where food becomes a conduit for gendered anxieties. Examining the configurations of diet in these five futures, we gain insight into a set of subconscious connections – between masculinity and carnivorism, femininity and restraint – which would not be noted outright for another century. In early feminist utopias, vegetarianism reflects ideals of feminine purity and passivity, ultimately reaffirming Victorian norms by reducing the utopian woman to the luscious fruit of a perfected world. They affirm vegetarianism as the ‘feminine’ diet, while only the male characters grieve their loss of carnivorism, restating an ingrained belief in men’s greater need for meat in their diet.

In the antifeminist dystopia, diet serves as a microcosm through which male anxieties around gender equality are revealed, as the disappearance of meat mirrors the erosion of masculine agency. Concerned that the women’s rights movement would turn the dynamics of subjugation onto men, these writers stage a crisis of appetite – both literal and libidinal. Planting a seed of social progress, they grow an orchard of forbidden fruit, where androgynous, Burne-Jones-faced inhabitants are left unable to desire one another. In these desaturated futures, appetite is not merely curbed, but redefined, leaving behind only the ghost of desire beneath a sterilised Eden. Here, what is eaten remains a timeless indicator of who holds power and who is left to hunger.

[1] Carol J. Adams, The Sexual Politics of Meat, 20th edn (Bloomsbury, 2014), p.51.

[2] Adams, p.58.

[3] T.C. Barker, The Dietary Surveys of Dr Edward Smith 1862-3: A New Assessment (Staples Press, 1970), p.32.

[4] Jean Pfaelzer, The Utopian Novel in America 1886–1896: The Politics of Form (Pittsburgh UP, 1984), p.141.

[5] James Gregory, Of Victorians and Vegetarians: The Vegetarian Movement in Nineteenth-century Britain (Tauris Academic Studies, 2007), pp.68, 162.

[6] Pfaelzer, The Utopian Novel, p.158.

[7] Edward Bellamy, Equality (D. Appleton, 1898), p.285.

[8] Pfaelzer, The Utopian Novel, p.141.

[9] Adams, p.58.

[10] Alfred, Lord Tennyson, The Princess (Edward Moxon, 1847), VII, ll.259-260.

[11] Murat Halstead, ‘Preface’, Mizora: A Prophecy by Mary Bradley Lane (G. W. Dillingham, 1889), p.5. All further references are to this edition.

[12] Heidi Hansson, ‘The Arctic in Literature and the Popular Imagination’, in The Routledge Handbook of the Polar Regions, ed. by Mark Nutall (Routledge, 2018), pp.45-56 (p.51).

[13] Katherine Broad, ‘Race, Reproduction, and the Failures of Feminism in Mary Bradley Lane’s Mizora’, Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature, 28.2 (2009), 247-266 (p.262).

[14] Pfaelzer, The Utopian Novel, p.141.

[15] Pfaelzer, The Utopian Novel, p.149.

[16] Jean Pfaelzer, ‘Dreaming of a White Future’, in A Companion to the American Novel, ed. by Alfred Bendixen (Wiley Blackwell, 2012), p.328.

[17] Broad, p.251.

[18] Sherry Ortner, Making Gender: The Politics and Erotics of Culture (Beacon Press, 1996), pp.28-33.

[19] Alfred Jost, ‘Research on the Sexual Differentiation of the Rabbit Embryo’, Archives of Microscopic Anatomy and Experimental Morphology, 36 (1947), 271-316.

[20] Adams, pp.4-5.

[21] Elizabeth Burgoyne Corbett, New Amazonia: A Foretaste of the Future (Tower Publishing, 1889), p.7. All further references are to this edition.

[22] Theophilus Savvas, Vegetarianism and Veganism in Literature from the Ancients to the Twenty-First Century (Cambridge UP, 2024), p.88; Adams, p.51.

[23] Pfaelzer, The Utopian Novel, p.147.

[24] Adams, p.5.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Savvas, p.64.

[27] Pfaelzer, The Utopian Novel, p.78.

[28] Eric Rabkin, The Fantastic in Literature (Princeton UP, 1977), p.140.

[29] Peter Sinnema, ‘Gender Trouble in the Hollow Earth’, ESQ, 69.2 (2023), 201-234 (p.203); Mrs. J. Wood (William Butler), Pantaletta: A Romance of Sheheland (Roy Glashan, 2019), ch.4 <https://freeread.com.au/@RGLibrary/WilliamMillButler/Novels/Pantaletta.html> [Accessed 1 March 2025]. All further references are to this edition, notated with chapter headings as page numbers are emitted.

[30] Mary Ockerbloom, ‘The Mysterious Author, or Who Really Wrote ‘Pantaletta’?’, Livejournal, 17 January 2011 <https://merrigold.livejournal.com/83980.html> [Accessed 1 March 2025].

[31] Justin Prystash, ‘Feminism and Speculative Fiction in the Fin de Siècle’, Science Fiction Studies, 41.2 (2014), 341-363, (p.343).

[32] Sinnema, p.219.

[33] Adams, p.66.

[34] Maurice M. Minton, The Illustrated American, vol. 6 (Illustrated American Publishing Co., 1891), p.107.

[35] E.M. Cioran, History and Utopia, trans. Richard Howard. (Quartet Books, 1987), p.87.

[36] Anna Dodd, The Republic of the Future; or, Socialism a Reality (Cassell & Co., 1887), p.81. All further references are to this edition.

[37] Pfaelzer, The Utopian Novel, p.81.

[38] ‘History of the ASPCA’, ASPCA, 2025 <https://www.aspca.org/about-us/history-of-the-aspca> [Accessed 15 April 2025].

[39] Minton, p.107.

[40] Bellamy, p.288.

[41] Clifford Smith, ‘A Forword’, A Crystal Age, by William Henry Hudson (E.P. Dutton, 1917), pp.ix-xix (p.xii). All further references are to this edition.

[42] Elana Gomel and others, ‘Romancing the Crystal: Utopias of Transparency and Dreams of Pain’, Utopian Studies, 15.2 (2004), 65-91 (p.76).

[43] Elana Gomel and others, p.76.

[44] Darko Suvin, Victorian Science Fiction in the UK: The Discourses of Knowledge and Power (G. K. Hall, 1983), p.33.

[45] Edward Garnett, eds., Letters from W.H. Hudson (Nonesuch, 1923), pp.174-5.

[46] Suvin, p.33.

[47] Richard O’Mara, ‘On William Henry Hudson’, Sewanee Review, 118.4 (2010), 575-585 (p.575)

[48] Prystash, p.355.

[49] Adams, p.48.

Comments

Post a Comment